The first time I stepped onto the sun-warmed sidewalks of Fort Worth, a faint wind carried the scent of mesquite, brick dust, and history. The afternoon light settled on the red stone facades and long verandas, while the rhythmic echoes of cowboy boots striking the pavement mixed with the distant hum of passing trains. This was not merely a visit—it was a journey across decades, back into the very fabric of Texas’ frontier legacy. What lay ahead was a full immersion in memory, craft, and the preservation of stories too significant to be forgotten. With a map folded in one hand and time unwinding before me, I began my passage through Fort Worth’s historical museums.

1. Stockyards Museum: Under the Neon Lights and Longhorn Legends

The Stockyards Historic District came first, a place where history breathes between saloon doors and wooden sidewalks. At its heart lies the Stockyards Museum, housed in the 1902 Livestock Exchange Building—a Romanesque revival structure whose very walls resonate with the commerce and character of Fort Worth’s cattle empire.

Stepping inside, the ambient temperature shifted as I crossed the threshold. The scent of old leather, varnished wood, and timeworn paper welcomed me. A dim, golden light lit up the displays—photographs, telegrams, branding irons, auction sheets—all artifacts of a time when Fort Worth was indisputably the center of the Texas cattle industry.

One exhibit held my gaze longer than the rest: a weathered desk belonging to a cattle broker, preserved with all its contents intact. Ink wells, blotting paper, a cracked ledger, and beneath it all, a hollow carved into the floorboards where cigar ash had accumulated over years. These quiet details, left undisturbed, lent the room a kind of presence—not haunted, but dignified, as though the broker had simply stepped away for a moment.

A small crowd had gathered near a glass case containing the 1908 lightbulb—one of the longest-burning in Texas. It glowed gently, a warm, amber flame that had survived more than a century. There was a reverence in the way people looked at it, a recognition of endurance both symbolic and literal.

I stood silently for a time, imagining the great cattle drives, the auctions, the clatter of hooves on brick, the smell of sweat and sun-warmed hide. Fort Worth was once known as “Cowtown,” and the Stockyards Museum does more than explain why—it makes you feel it.

2. Texas Cowboy Hall of Fame: Echoes of the Arena

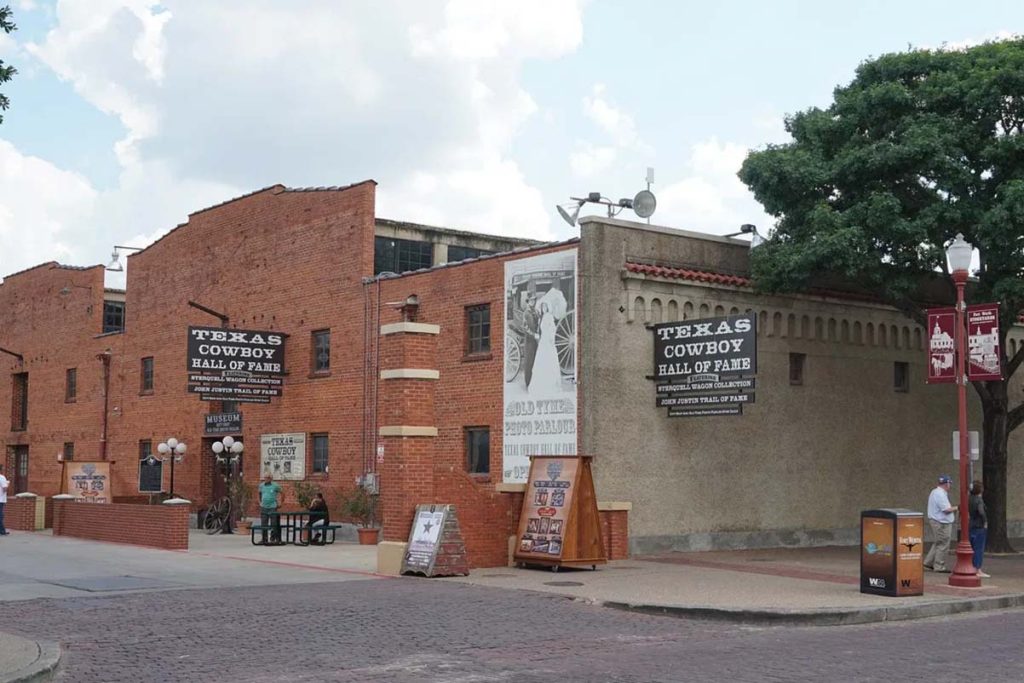

Just a short walk from the Stockyards Museum, within a historic horse and mule barn originally constructed in 1888, stands the Texas Cowboy Hall of Fame. The scent of hay still lingers faintly beneath the scent of polished wood and fresh varnish, and the echo of hooves, long since silenced, seems somehow present in the rafters.

Each inductee in this hall is honored with a plaque and personal artifacts—ropes, saddles, boots, photographs—testaments to grit and glory. Some names I recognized from rodeo posters and news stories, others from whispered mentions in roadside diners. The diversity of faces—men, women, Native American cowboys, African American ranchers—reflected a richer and more complex story than the mythologized cowboy often seen on screen.

In the adjacent exhibit rooms, the Sterquell Wagon Collection caught me by surprise. An entire hall dedicated to horse-drawn vehicles—stagecoaches, chuckwagons, surreys, and doctor’s buggies. Each had a story: a wedding coach used in 19th-century Galveston, a medicine wagon that once rattled through West Texas towns. Their craftsmanship was astonishing—iron-rimmed wheels hand-forged, canvas tops stitched with care, woodgrain polished to a gloss by both age and admiration.

I took a seat on one of the benches opposite a preserved Wells Fargo coach, the leather cracked but firm, the interior suffused with ghosted voices. For a long while, I watched others walk past, their movements slow, as though time itself had slowed to match the pace of a wagon.

3. Fort Worth Museum of Science and History: The Fusion of Past and Possibility

Leaving the Stockyards behind, I made my way south toward the Cultural District. The shift in atmosphere was immediate—broader boulevards, tree-shaded sidewalks, families strolling beneath banners fluttering in the warm breeze. The Fort Worth Museum of Science and History stands here, its modern facade of glass and stone belying the age-old truths housed within.

Though known for its planetarium and children’s exhibits, it also contains one of the most evocative local history collections in the city. The “Cattle Raisers Museum,” nestled within the main building, drew me in like a magnet. Walls lined with archival images, interactive maps, and branding iron collections told the economic and cultural story of ranching across centuries.

One particular installation allowed visitors to record their own family’s ranching history, should they have one. I stood listening to a woman’s voice narrating her grandfather’s story, accompanied by a faded photo of him holding a newborn calf beneath a West Texas sky. Stories like his were scattered throughout, each one a thread in a tapestry woven from weather, soil, tradition, and livestock.

In another wing, a restored log cabin sat in the middle of the gallery floor—transported piece by piece from its original location in the Panhandle. Inside, the smell of pine lingered. Handmade quilts lay atop narrow beds. Shelves held soap molds, old tobacco tins, and well-worn Bibles. There was no attempt to romanticize pioneer life—only an invitation to understand it.

Time passed unnoticed within these walls. Outside, the light had turned honey-colored, and the museum’s stone exterior glowed against the early evening sky.

4. National Cowgirl Museum and Hall of Fame: Grit, Grace, and Legacy

Across the plaza stands a museum whose mission is as distinct as its architectural lines—the National Cowgirl Museum and Hall of Fame. Entering beneath its arched facade, I was met with an elegant mix of marble and terra cotta, light pouring in from clerestory windows.

Inside, the atmosphere was reverent yet vibrant. Photographs of women rodeo champions, ranchers, artists, and writers lined the halls. Some faces stared with quiet defiance, others with laughter behind their eyes. All had lived lives of tenacity, innovation, and strength.

An exhibit dedicated to Annie Oakley showcased not only her legendary sharpshooting but also her advocacy for women’s rights and education. Her letters, written in neat cursive, revealed a mind as sharp as her aim. Another installation chronicled the life of Temple Grandin, with audio excerpts from her writings, models of her livestock-handling innovations, and video clips of her speaking to ranchers and students alike.

A particularly moving gallery featured women who had shaped frontier medicine—midwives, healers, and nurses who carried herbs and courage across hostile land. Their tools were displayed beside brief biographical sketches. Many of them had worked in obscurity, their stories nearly lost to time. Here, they stood illuminated, finally seen.

Upstairs, the rotunda honored living inductees, and I found myself drawn to the glass panels etched with names—each a legacy, each a lifeline to the American West as it truly was and remains.

5. Log Cabin Village: Living Histories Beneath the Oak Trees

As morning light filtered through sycamores and post oaks the following day, I arrived at the Log Cabin Village, a living history museum nestled just south of the city’s center. A winding path led past cabins relocated from across North Texas—each restored to its 19th-century form.

Within each structure, costumed interpreters demonstrated traditional crafts and domestic routines. At the blacksmith’s forge, the air filled with the metallic tang of heated iron and rhythmic clangs of the hammer. Sparks flew upward like fireflies as the smith shaped horseshoes with effortless grace.

In a nearby cabin, the smell of cornmeal and woodsmoke drifted out the open door as a woman in a gingham apron stirred a pot of beans over the hearth. Quilts hung on walls; feather beds were neatly made; shelves bore jars of pickled okra and wild plum preserves.

What struck me most was not just the authenticity, but the intention behind every detail. This was not a theme park version of history—it was a reverent re-creation, based on diaries, tax records, oral histories, and archaeological finds. Children churned butter, adults asked careful questions, and the line between participant and observer quietly blurred.

Seated on a rough-hewn bench beneath an old pecan tree, I watched a group of schoolchildren practicing penmanship with quills and ink. The past, here, was not frozen. It breathed, moved, taught, and endured.

6. Sid Richardson Museum: Oil Barons and Brushstrokes

Tucked away in Sundance Square, a quieter kind of history unfolded inside the Sid Richardson Museum. The building’s exterior—red brick, subtle signage—gave little indication of the treasures within. The scent of linseed oil and aged canvas lingered just beneath the clean air of climate control.

This museum is dedicated to Western art, particularly the works of Frederic Remington and Charles M. Russell. Their paintings, rich in tone and movement, conjured a world of cowhands, Comanche warriors, buffalo hunts, and campfire scenes. Though often romanticized, these images held deeper truths—subtle tension in the faces of subjects, honest renderings of hardship and survival.

The museum’s namesake, oil magnate Sid Richardson, had an eye for authenticity. The collection reflects not just a fascination with the mythic West, but a collector’s belief that these stories mattered. Docents spoke quietly with visitors, illuminating the techniques of the artists, the provenance of the pieces, and the historical contexts behind each frame.

A portrait of a solitary rider, silhouetted against a rising dawn, seemed to capture the essence of Fort Worth’s historical journey—a figure pressing forward, forged by history, wrapped in solitude, defined by motion.

7. Walking Between Centuries

What had begun as a tourist’s itinerary evolved into something deeper, more resonant. Each museum, though different in scope and structure, offered a window into the soul of Fort Worth. The city’s past is not ornamental here. It is preserved, curated, interpreted, and—most importantly—lived.

Long after the museum doors closed each day, I found myself revisiting their stories in quiet moments—on park benches beneath creaking trees, or sipping coffee in dimly lit cafes where antique clocks marked time with patient hands. Fort Worth does not shout its history. It speaks in tones of brass and oak, of weathered leather and wrought iron, of fiddle strings and hoofbeats.

Evenings arrived with cicadas singing in the dusk and the scent of barbecue hanging in the twilight. Streetlamps flickered on above cobblestone lanes, and the city, as it always has, kept on remembering.